The Millions

I never thought I’d contribute to the vast canon of writers-on-writing essays, but here is one, called ‘There is No Handbook for This’ that I wrote about second-career writers (like me) for The Millions.

I never thought I’d contribute to the vast canon of writers-on-writing essays, but here is one, called ‘There is No Handbook for This’ that I wrote about second-career writers (like me) for The Millions.

May 2015

The artistry in travel writing is in how deftly one can dance between two seemingly disparate things. We must disappear into our new surroundings while maintaining the detachment that is required of the observer. Travel writing is about immersion, but it is also about being a stranger and an outsider. The task is to absorb and be absorbed, all at the same time. When we land in a new place, we instinctively peg the awareness needle to high. Our senses are on, and we use them like sharpened tools. The sun on our neck has a revelatory new heat. The clatter of spoons on coffee cups at the café has an unfamiliar din. As our feet propel us through the throng on the boulevard, we blend in while we simultaneously stand out. From the second we land in a new place, it is that 360-degree sense of discovery we seek. This is obviously a sensation we can never experience at home. Right?

Wrong.

This surprising truth was revealed to me when, recently, I had to cancel a longed-for solitary escape. At the last moment, the need to stay put superseded the need to travel, though the latter was certainly all-consuming. In northwestern Connecticut, the segue from winter to spring was (literally) glacial. Snowdrifts hung around on my lawn throughout April and pockets of ice lingered in the walkway cracks well into tulip time. It had been the season of turning inward, of driving to Boston to check in with aging parents, of pressing forth on a book tour despite weather that repeatedly worked against me. I had been socked in physically and emotionally. There was always work to do, meals to cook, cars that needed oil changes, and spring had ushered in a long, costly to-do list. Chips of paint the size of dinner plates tumbled from the house, and my yard was a wreck.

I was ready to break loose. So, one reservation at a time, with the anticipation exciting me to sleeplessness, I planned my escape to Portugal, a country I last visited in 1991. Then life intervened, as it does, and I cancelled the whole trip. (note: ALWAYS get travel insurance)

Events had pushed my hand but I turned this into an opportunity. Rather than feel trapped or thwarted, I decided to bring the same journalistic curiosity – the engine of all my travels – to my own neighborhood and daily routine. Senses pegged, I pretended to be on assignment, and on alert to all manner of discovery. The fact that I lived here meant that I easily submerged into my immediate surroundings, so the first task of the travel writer was automatically covered. The second one was my challenge: to gaze on my world – the one that seems so small to me – as a visitor from Portugal might. I wanted to be an outsider in my own realm.

How had I never felt the onrush of spring? If I had been writing from France or Russia or Norway, I would have gushed about the aroma of lilacs or the swaths of tulips that lined the country roads. There, great clouds of apple and cherry blossoms would have seemed different and surely better than the ones in my own backyard. It seems I’d never given this place a chance. I thought I could only see the world from elsewhere, but I marveled at the same things I apparently was blind to at home. Silver birch and giant pines – had they always been here, right beyond my driveway?

I was so proud of this earth and its brave recovery after the frozen devastation of winter. I walked and walked, taking in my small town as if I’d just landed there for the first time. Sometimes I took my dog, other times my daughter joined me, others I met friends I love and we kept our chatter low as we faced the rushing river at Steep Rock.

For once I read the menu at the bakery, where I order the same muffin and coffee every day. The scent of cinnamon and yeast was as intoxicating as any patisserie in Paris. I closed my eyes and inhaled, the sense of newness magnified by the reality: this is home. Daylight filtered through the young and still pale leaves, but the trees were filling in quickly. Lots of growth sprouted along the river, the one I had never before approached. A man asked me if I was looking for morels. “I come here every year to pick them,” he said.

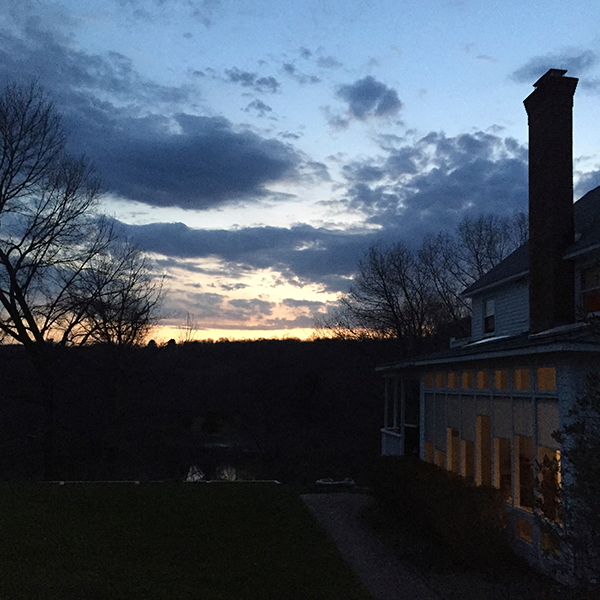

Gold forsythia and rich earth. Violets that blanketed the low, damp crevasses. The lake, blue and at last unfrozen. My husband’s sculpture released from its burden of snow. The sky over my house as night fell. My jacketless daughter, strengthened by another winter in New England. We are hardy. All this beauty erupts each year, and I had never even noticed.

This is what happened when I brought my curiosity home. It was so simple to watch and to finally see. Travel writers are naturally attuned to details, so this is an exercise I recommend to everyone who observes for a living. Always be prepared for amazement, because it’s everywhere, even at your own front door. You don’t need an airplane to carry yourself forth into this spinning world.

This exceptionally punishing New England winter is, at long last, fading out. Grass is beginning to reveal itself in ash-colored patches around the yard. The snowdrifts that line both sides of the driveway are blackened from exhaust but slowly disintegrating into lower and lower ridges. I hope by Easter, the last chunk of snow will melt into the last drop of water and the great Ice Age of 2015 will be behind us.

It has been five months since 100 Places came out. Promoting it, discussing it, signing it, sending it out, writing articles about it, answering questions about it – this has been my raison d’être. I love the exhilarating aftermath of writing this book – the tail end, when I demonstrate my belief in it, and tirelessly (shamelessly, too) hope others will believe in it as well. It’s a very simple equation: I wrote it and I want people to read it too, so my job has been to get it into as many hands as possible.

But besides the talks I’ve given and bookstore events I’ve traveled to, it has been perhaps a little too quiet these last bitter cold months. The incessant snow and frigid weather has forced me inward. I’ve cosseted myself in the easy cocoon of my home, next to my notes and computer and books. Working all day. But not traveling. Which is a problem, because for a travel writer, these two things are one and the same. Lately, I’ve been waking up with a need to wander.

It’s hard to glamorize travel these days. It’s absolutely hideous and in some ways, degrading. Airports are ice cold bunkers manned frequently by staff that clearly despises you. Security lines are endless and humiliating. We are herded up like tranquilized animals onto planes where the too-small seats are stained with dried liquid of unknown provenance. They serve crappy food that you have to pay for, and you eat it off flimsy trays. The horror.

And…I live for it. I love this ritual of departure in all its poetic misery, because on the other side of it is an arrival. No matter where I’m heading, leaving brings fulfillment and if I’m lucky, a story.

The reality is that “elsewhere” is right there for the plucking, and I love how changed I feel that split second after I’ve clicked on “purchase ticket now.” It provides a singular rush, to cross over from the torpor of routine into that supercharged state of anticipation. Hallalujah, I’m on my way. This deliberate and sudden act of discarding my desire for comfort and complacency proves that it isn’t a real desire after all, but is an obstacle to the act of living. And for a travel writer, it is an impediment to the very important act of working, too.

So today, I bought a plane ticket to somewhere I haven’t been for 20 years. I will bring a stack of Field Notes and all kinds of pens and pencils, all tidy in a Ziploc bag. I’ll meet people and talk and write it all down, as I’ve done in Peru, Haiti, Russia, Indonesia, Sweden, and many other countries, as well as France, France, France. When I get back, gorgeous springtime will be in full bloom and the lawn will be fragrant and green again. I’ll plow through the books I’ve accumulated all winter, and read them outside in the sun, alongside my dog who can finally get up off his rug and run.

My work isn’t done on my book. When I get back from my trip, I’ll still be a devoted and passionate author, reading from it and believing in it, tirelessly, whenever and wherever I can. But behind the lectern, I’ll be that much richer. I’m always more alive when I’m in motion and as long as I am breathing, I’ll never stand still for long.

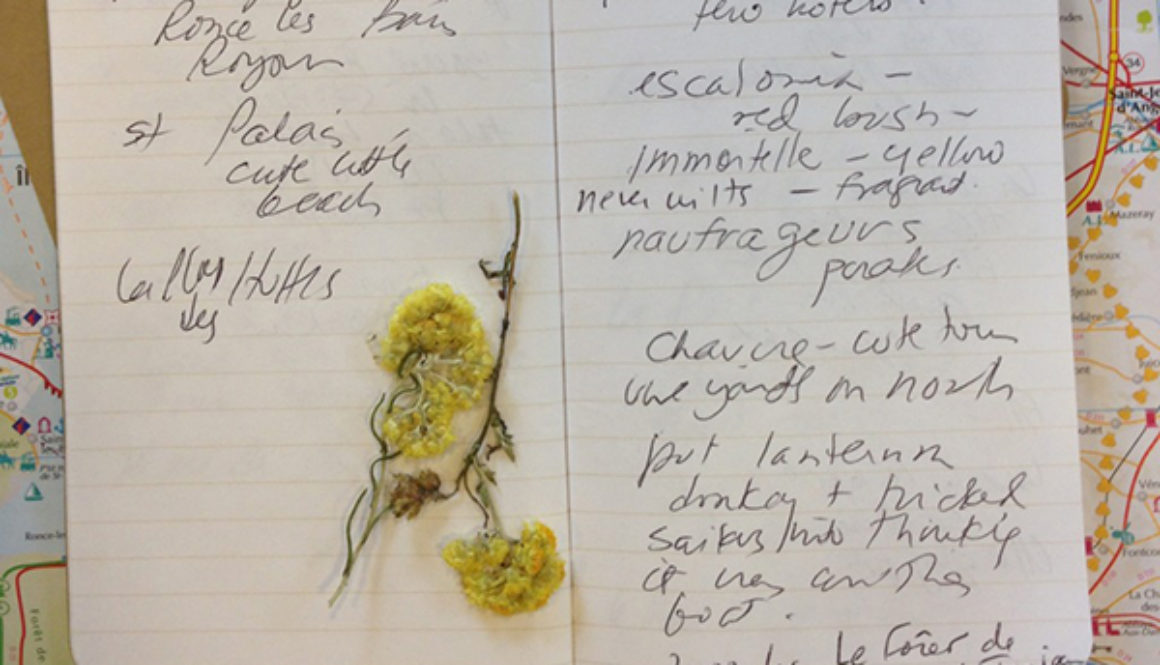

No sooner had I handed in the manuscript for 100 Places in France Every Woman Should Go that I finally had a much-postponed lunch with an old friend. I had not seen her throughout the several months I spent in a dark cave writing, and behind the wheel of a little Citroën in France, researching this book. I filled twelve Field Notes books with scribbles, sprigs of rosemary, splashes of café crème. In my office, I closed the drawer full of them for the last time. I was – happily – done.

I’m not sure how this woman escaped my radar, since I had canvassed literally dozens and probably more accurately hundreds of people, mostly (but not all) friends (but all of them friendly), for their ideas on France.

“Great news about the book.” she said. “I hope you have a chapter on La Rochelle.”

“Well….,” I began.

Two weeks later, I was at a cocktail party, chatting with an acquaintance, who repeated that sentiment. “You know my favorite place? La Rochelle!”

La Rochelle is an idyllic city on the Atlantic coast, edged with medieval towers, through which weaves a web of arcaded sidewalks. It is also where you take the bridge over to Île-de-Ré. Which is in my book. La Rochelle is not.

These conversations happen often, practically every day. I like them. Lists are random events, and there are many more than 100 places for women to go. Doubts are part of the writer’s psychic landscape, and this book has given me my share of them. Why did I choose a tiny absinthe bar in Antibes for a chapter, and not the gemlike town of Uzès? The latter is an up-and-comer, the “new Aix-en-Provence” as it’s been described to me, and many people have asked – hoped – it is included in my book. It is not.

Sometimes, I wish my editors had assigned me a book on 200 places. Even 1000 places would have been easier than culling this magnificent country down to a mere 100. But the list had to be an even 100 and every one of them had to have a reason and purpose. I hope you will see a line that threads among the narratives and stories in this book. Each of the 100 had to be somewhere I love, or involve an activity that I seek. Hiking, for example. Searching for beauty. Eating chocolate. Finding stillness. Drinking rosé in the middle of the day. The 100 also had to include those places where women made their mark, cast their shadows or shed their light. There are thousands in France. Hence, the absinthe bar. This was a chance to tell the story of this potent spirit, so crucial to French creative life in the late 19th century, and women’s great role in selling it, drinking it, and even abusing it.

There are a lot of memories in this book, and I’m lucky to have a lot of them of France. It would not have been possible for me to write this book without my own extensive history there. I went through diaries, photos, documents. I found the leasing agreement for our second apartment in Paris, on the rue du Pont aux Choux in the Marais. I always pass by that apartment building when I’m in Paris. Now, there is a super chic lingerie boutique called Odile de Changy across the street. Both the old apartment, and the new shop are in my book.

One final word about putting this book together. I kept a list of words and expressions I wanted to avoid, and added to it frequently. I may have overused the adjectives “dazzling”, “gleaming” and definitely “gorgeous”, but I avoided the term “City of Light” as a euphemism for Paris. To me, it is the city of dreams.

And here are two links to buy the book:

Indiebound and Amazon

After my first research trip for 100 Places in France Every Woman Should Go, I learned to pack an extra suitcase. A duffel bag from REI folded into its own little zipper case that slips right behind the rest of the stuff on the way over. The extra baggage fees are awful, of course, but 70 euros is a relatively small sum to pay to carry home postcards, flyers, business cards, hotel stationery (guilty – I love the envelopes in France, and they are useful for gathering research- more below) books, trinkets, a random bottle of Calvados, those pretty tins from Belle Îloise, a tube of Homeoplasmine skin ointment, mascara from Serge Lutens, something from the flea market. Much as I’d like to, I’m not talking a Rick Owens leather coat – my idea of fashion perfection – from his store on the Palais-Royal or something more colorful from the Dior boutique on Avenue Montaigne. No, for designer extravagance, I’m strictly stateside and usually on-sale.

When I open up my extra bag at home, even something I’d picked up a couple of days before incites a rush of memories, even a bit of nostalgia for the person I was earlier that week – the woman who woke up early on Île d’Oléron and rushed into a brocante, and scooped up 3 euros in change from the bottom of her purse for an aging cookie tin. The woman who stuffed bits of paper into an envelope in her bag, ticket stubs from churches and museums and cartes de maison from little stands next to the cash registers at bakeries, boutiques, cafés and flower shops. All this, so I can remember where I was those endless days traveling around France.

It all added up to something: my book. I bought a pamphlet at the Saint-Pierre Chapel in Villefranche thinking, maybe I’d include it in a chapter on Jean Cocteau? I did. I gathered post cards at Sainte-Chapelle after a concert there, where the sun pierced the stained glass windows upstairs, fracturing sunlight into a million glowing shards. Would I consider an entry on seeking out music in Paris’ churches? Yes, I would. I grabbed the pretty card at Odile de Changy, a lingerie boutique on rue du Pont aux Choux, the narrow street in the Marais where Mark and I lived when we were married. What about a story about how to shop for the most important part of dressing? Okay, done.

In this respect, writing this book was like writing my yet-unpublished novel. Back then, I had a dry-erase board full of ideas, arrows, categories, subcategories. Characters big and small. Plot lines underlined and circled, names in big red letters. This time, I hung a large bulletin board and stuck totems, maps and mementos into collages on the cork. When that real estate was taken, I spread out, tacking things right onto the wall. Some were names or places I scribbled onto index cards. Camille Claudel. Simone de Beauvoir. Colette. Vézelay. Étretat. Bordeaux. Others were colorful reminders of the places I’d been, enchanting enough to remember, enticing enough to urge other women to go there. A ticket stub from the Musée de la Chasse in the Marais. Where and how could I fit that in to a list of 100 places? Somehow, I did.

As for the stuff, I used it – the creams, the scarves, the lingerie, the Calvados. The bottles and bibelots and antique postcards from the marchés aux puces are another story. They are dispersed here and there, in my office or home or given as gifts, keepers of two stories. The one about where it came from, and the one about the woman who saw it, bought it and took it with her.

A year ago, I had not yet begun to research my book, 100 Places in France Every Woman Should Go. In fact, I had a beautifully empty slate, a 4-week residency at Ragdale, a memoir I was itching to write there and a novel I was desperate to revise and get back into the market. Hard to believe, in hindsight, that I hesitated for one second when my friends at Travelers’ Tales asked me if I’d be interested in taking on France. That week of deliberating was a futile exercise in not trusting what fate had in store for me. Now, almost a year later, after I’ve edited and re-edited and re-edited the manuscript, the book is at the printer as I write this. The list is final – at least for this project. In this context as with most obsessions, letting go is tough.

And yet, I am still researching France, ever surprised by the colors of the shutters on whitewashed coastal houses. I still hope to try every cake and local pastry, and I still want to follow France’s great women whose footsteps continue to resound all over the country. In towns like Poitiers where the teenager Joan of Arc was vetted for the almost-king she had come to save (and as the Commander of his army, did) by driving the British out of France.

Mark Twain’s biography of her is sensational – he was obsessed by Joan and after writing this book, so am I. Poitiers is also where Eleanor, the Duchess of Aquitaine, as Queen of France and then of England, still ruled over her vast ancestral lands, entertaining with medieval royal flair from the Palais de Justice that still stands today.

One of France’s less-frequented regions, Poitou-Charentes, is France for women in a perfectly compact microcosm. It extends inland from the Atlantic coast above Aquitaine, is geographically diverse, there are history, wine, and some of the most pristine expanses of sand in Europe. I’ve just returned from a delirious spin around its beaches, islands, and ancient towns of Cognac, Poitiers, and La Rochelle.

Several, not enough, of these places are in the book – it’s kind of the tragic nature of lists that not everything makes it, and by far the hardest part of writing this book. But some things did: the laid-back islands strewn with bike paths, salt flats and painted shacks, and of course Poitiers that stands in the shadows of its great women, Joan and Eleanor.

It’s still astonishes me: how everything coexists so beautifully in a place like this. How we can walk the medieval streets laden with history and buy roses at the market in the morning, drink cognac from the source at lunch, stroll hot beach sands in the afternoon and relax with a plate of oysters in the evening.

Last year, months before I was asked to write a book about France for Travelers’ Tales, I was explaining to a friend why I – let’s say – strongly encouraged my daughter to study French. For me it was simple. “Every girl should live for a while in Paris,” I said. Another person in the room looked at me with disapproval. “That’s kind of sexist,” she said.

I tried to defend myself and I will do so again here. I know this. Men love France as much as women do. My husband, when he was still my boyfriend, encouraged me to take a break from my job at ABC News 20/20, lift up stakes, and move with him, just for a little while, to Paris. He is an artist, I’m a journalist and our professional freedom allowed us to heed the call, as Americans have been doing for centuries. We returned home after four years and now, a couple of decades later, with the rosy filter of hindsight, we still look back on our Parisian life together as, in some ways, perfect.

By saying that I wish for my daughter a spell in France does not mean to suggest that I don’t wish it for my son, as well. But I believe it changes a young woman in ways that it might not change a young man. I learned to eat well, walk tirelessly, and allow the singular elegance of Paris to penetrate me, sink into my bones, strengthen my spine and resolve. Walk with my head up so as not to miss something spectacular. No woman, not even the great beauties of France, could ever compete with Paris and that both keeps us humble and at the very top of our game. We seek it out as we seek more idealized versions of ourselves.

In the fall of 2013, I took the assignment to write “100 Places in France Every Woman Should Go.” I was determined to make this a book for women and about women, and to add some history and observations behind the familiar tropes of City of Light, perfume, champagne, châteaux and sinful desserts from which the clichés about women and France are derived. I wanted to combine memoir, travel advice, deep writing and just enough awe with reflections on some of the country’s great—or interesting—women, starting with Joan of Arc up through Catherine de’ Medici, to Edith Piaf, Amélie and even Carla Bruni. I like her music, and when I taught French, I made the kids memorize “Quelqu’un m’a dit”. I wanted to focus on what captivates even the most sophisticated traveler to France, and tell the stories behind the places. I won’t necessarily inform you of all the ways to get to Versailles, or when to go there, but I will give you my take on why we have such an enduring fascination with Marie Antoinette, the last queen to reside in the palace. Similarly, Veuve Clicquot is more than just a yummy luxury champagne. It’s a brand (and a place – in Reims) imbued with story, due to the 27 year-old widow who, in the late 18th and early 19th century, made the company what it is today.

I loved writing this book. I traveled to France and often, rented a car, drove the autoroutes and through medieval villages, in the sun, the rain, and the snow. Alone. But I called upon my memories from when I lived there, and the many, many times I visited, before then and since. Sometimes as I was writing, memories came face to face with new revelations. The sense of discovery, then and now, is unchanging and provokes me to notice scents, flowers, the colors of the sky. Sometimes, I ran out of words. Often—when I stood on the beach at Bidart, or sampled Calvados in the middle of an apple orchard in Normandy—I ran out of power. The emotions caused my wiring to short out. This is what France will do. Confront you with the eternal so gently and so forcefully, one can feel almost not of this earth.

I took thousands and thousands of photos, some of which I will be sharing right here. But I leave you with the only picture I’ve ever been able to salvage from my first trip to France in 1979. I look 35. I was 18. I have better taste in sunglasses today and in other ways have changed. Paris has not. With any luck, it never will.

Paris 1979

The town of Villefranche-sur-Mer seems to be rather mum on the subject of its most famous residents, the Rolling Stones. They lived there during the summer of 1971 in the Villa Nellcote, a mansion overlooking the Mediterranean, and recorded much of Exile on Main Streetwithin the seclusion of its iron grates. This was chronicled in folkloric, debaucherous detail in Keith Richards memoir, Life.

This morning, I climbed the hills to the villa, whose whereabouts I knew from another life and whose gates are now lined with thick nylon canvas to keep people like me from looking inside and imagining that summer. Okay, I felt like a bit of a trespasser, even though I stayed safely on the sidewalk. I can’t say it’s all about the music, although the music was something and I still know EOMS from start to finish. My mother used to go to the record store in town and pick out a few that looked worthy to pile under the tree for me and my 3 big sisters. The Christmas of 6th grade, I got Exile as well as The Harder they Come by Jimmy Cliff, which I think I traded for Something, Anything by Todd Rundgren with one of my sisters. Being more in the Beatles camp, with a father who played Joan Baez and Johnny Cash and siblings very much into CSNY, I could give or take the Stones’ music. But this record was something unusual, especially the acoustic side, with its underwater/country guitar riffs and searing vocals on songs like Torn and Frayed. Later, it would become the soundtrack for a lovely stretch of time during my senior year of college but for now (back then), I just liked it better than the Stones of Satisfaction.

The house sits on a quiet street, quite dignified behind the impenetrable security zone. It’s almost as if nothing ever happened there. I wonder how the house holds its history all tight like a secret? How does anything or anyone hold its history?

When I get ready for a trip, I put different parts my life inside of a container. Toothpaste, a bathing suit, a raincoat, trousers for day and night, too many shoes. Never enough tank tops (which I wear under the sweaters I usually forget). What ends up in my suitcase is always an accident and depends more on my mood when I’m packing than what I will need when I get there. I stack my belongings with lots of haste and very little good sense. Last time I was in Italy, I began to feel bruised by the winds off the Grand Canal so I found a parka on sale on the Frezzeria. It was mauvy-gray, dead last on the store rack and on my list of wearable colors, but it kept me warm as I lurched across the Piazza San Marco.

What you need, who you are, who you want to be and who you might become. These are questions that may be either asked or answered inside of your luggage, even on a short jaunt. I remember my first visit to the Cote d’Azur when I was 18. I wrote an essay for Vogue about that summer, how my sad little duffle bag contained nothing appropriate for nights out in Monte Carlo. So I bought a drapey white halter dress and high-heeled sandals that were perfect for the casino. When I balled up the dress and wedged the shoes into my bag as I was leaving Nice, both were well-worn and I was somewhat changed. From that time on, although I have forgotten everything from underwear to hiking shoes even for a hiking trip, I always pack evening clothes, down to the footwear. So in honor of that memory, I tiptoed in black suede heels down the Promenade des Anglais, past the apartment I lived in that summer, to dinner and a tour of the great Hotel Negresco – stately and unchanging.

Sneakers, though, were tied sensibly on my feet for a stroll around Old Nice to smell the pissaladière and socca and tubs of olives at the market. I emerged from the elevator up at the Chateau de Nice and got a full-frontal panorama of the Baie des Anges. Lunch was a dreamy, rosé-soaked respite at La Reserve, on the cliffs near Nice’s port. By the time I got to the magic village of Villefranche, I yearned for a rest and a spot of contemplation time. Returning to places can have this effect. I see things both through the lens of all my years, and that of the person I once was. I had stood on this shore for the first time when I was all of 18, the age of my oldest child. I untied my shoes to settle into Cocteau’s room (22) – starry, blue, serene – at the Hotel Welcome, threw open the French windows. I unzipped my suitcase to search for something that suited the woman I was right then. I had stacks of cargo pants, a pair of skinny jeans, leather trousers, a couple of unworn dresses, including the one I wore to my 50th birthday dinner. High heels, flat heels, flip flops. My favorite navy blue fitted blouse. There was my pleather skirt, the full dark brown one, folded into quarters. Why had I packed that? Because you never know. I zipped the bag back up and turned around to look at the sea.

I have a new and exciting project – a book called, “100 Places in France Every Woman Should Go,” to be published by Travelers Tales in Palo Alto, CA in 2014. This is not a guidebook per se, but more of a bucket list with a women’s perspective for people who love France, or might yet fall in love with it. This is not a simple task, as I can name 100 places just in the Marais, Bastille and Oberkampf neighborhoods of Paris where il faut aller. Without divulging any of my choices, I can safely say that Provence – the area from Arles to the Alpilles, and down along the Mediterranean coast from Frejus to Menton on the Italian border is likely to figure prominently. Americans are drawn to the James Bond sexiness and insouciance of the South of France as much as the act of puttering around the markets to inhale the scent of persimmons picked this morning, and a cool glass of rosé at lunchtime with fish just pulled from the sea. Not to mention the cinematic perfection, which filmmakers have been making good use of since the days of Louis Lumière.

So far, I’ve been writing, writing, writing. Taking notes on the color of the sky. Picking a cluster of tea olive blossoms that I press into my notebook. The clouds thicken up on the road to St. Paul de Vence while I’m at the wheel of a 1968 white Mustang convertible, the same one driven by Honor Blackman when she was 007’s foil in Goldfinger. I round one hairpin curve after another and the sea disappears into the distance, as does the awareness of my role on earth. I’m a mother, a wife, a daughter, a friend but right now I’m all focus and drive. There is one road underneath and my mind is on only it. Get there safely, note the shifts in the air now that the temperature has dropped, press the brake. Note the sight of the medieval walls. Note the pattern in the footpath. Note the banyan tree near the Colombe d’Or.

It’s not a hard job (well, making a living and getting people to return your e-mails can both be rough) compared to telephone pole repairmen and triage nurses. But the work comes with me everywhere I go. Now, my mind ticks as I start to collate the search for 100 places in France, my print articles, the stories I want to write, the other unknown places I wish to know. As I descend to Nice, then settle onto the indoor terrace in my sea blue and green room at the Hi Hotel, the ideas are slamming onto the walls of my brain. The day spent galavanting along the Riviera in a sports car was an gorgeous one, but it was always and ever a workday.I’m not a car person and neither is my husband. He has a pickup and I have Toyota, and we use them to take us places we need to go, usually to the Stop & Shop for groceries. But today, the question looms: is this why people love to drive? There are wheels below, a sky above, a mission to accomplish in getting there, wherever ‘there’ is, and little else.

Except for writers who by definition, are always working. Even a stop at the CVS for a pack of gum is a chance to observe human behavior, sponge it all up, glean snippets of conversation.