I’m here on the Côte d’Azur to gather background material for some magazine articles, in the place where luxury came to nestle over a century ago in custom-built mansions among wild jasmine and palm trees. The odors of rose and citrus seem to be brewed in the coves that carve giant scallops into the coastline. It’s the same now as it was thirty years ago, when I first went to Nice. I had just completed my freshman year at Princeton where the ghost of F. Scott Fitzgerald, class of 2017 (dropped out, actually), floated for better or worse through all of us. It was part of Princeton lore to imagine the soon-to-be-great young man from Minnesota traipsing along Prospect Street and we joined him in these wanderings. His was a story with which we all became familiar: about his tragic wife Zelda, his relationship with his editor Maxwell Perkins, all freshly told by his biographer (another Princetonian, though from more recent years) Scott Berg.

He wrote about the gilded age and it was the side of paradise that was seductive because it was no more. Hard days had come and the good times had passed and how we craved them. How we crave them still.

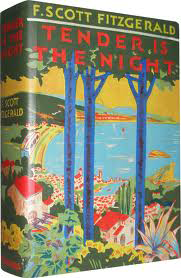

At one time, I became aware of the great scholarly debate: The Great Gatsby vs. Tender is the Night. If the first is considered the most perfect novel ever written, the second (his last book, written after Zelda was hospitalized for schizophrenia) can be deemed a hot and craftless mess. I’ve always preferred the latter precisely because of its flaws: they create its own harmony. It’s also a richly descriptive novel (count the plants in the garden chez Diver in the first three paragraphs of Chapter 6: lemon, fig, lilac, iris, rose – and the corresponding colors) and from the first words, a classic (think Henry James, Edith Wharton) in the American in Europe genre. Despite the melancholy and infidelity and bleakness that unfolds so shatteringly, Dick and Nicole Diver threw great parties, with heirs and novelists and royalty and ne’er do wells. We didn’t want to be them, but we wanted to know them: “to be included in Dick Diver’s world for a while was a remarkable experience,” the narrator says early on in the book, which I re-read on the Air France flight over.

Late in the afternoon, my car pulled up alongside the Belles Rives (once called Villa St. Louis), Fitzgerald’s former rented house in Juan-les-Pins, which is now a plush hotel. Some of his original furniture – art deco tables and chairs which German soldiers hadn’t destroyed or used for God-knows-what during the war – remains, as does the building, all spruced and polished to perfection. From the terrace above the cove, you can see the islands across the way, and imagine Gerald and Sara Murphy, on whom Fitzgerald based the characters of the Divers and to whom he dedicated the book. Most beautiful by far was the dining room, which was his office. It is lined with large windows that look out to the terrace which give way to the sea. There, inspiration is a tactile thing. Magic + talent = masterpiece.

It was impossible to expel the man from my thoughts later, over dinner at the Hotel Royal Antibes. Fitzgerald’s Riviera – the rose-colored hotel and long beach afternoons – was not simply his playground. It was a fertile field to be tilled and harvested many years later. Tender is the Night was published in 1934 – eight years after he left the Riviera.